One important target this year was the

Yakutat Icefield. This is one of the most rapidly changing glaciated areas in Alaska. All of the glaciers are at quite low elevation, and the icefield will most likely disappear within this century. We published a

paper a few years ago that showed that even without further warming, the icefield is essentially doomed.

Here is a prediction that we made in 2013:

This is a map view of the Yakutat Glacier, which is part of the icefield. Colors indicate ice thickness with red being the thickest ice (around 600 m). The lake is shown in white. The retreat we had predicted by 2020 has almost happened already. Below is a picture from the eastern margin (right terminus above). The two tributaries still join, but probably not for much longer.

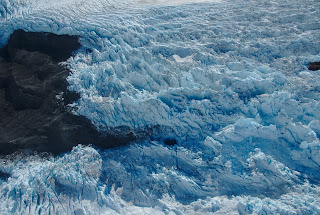

And here is the western terminus. Again, as predicted, the two tributaries still join, but just barely.

The reason for this rapid retreat is that even the highest elevations on the icefield are just at about 600 m asl, which is quite low. So all the snow melts, even at the higher elevations, as seen in this image:

The melting slowly uncovers previous years snow accumulation. It is like cutting through a layered cake and it shows the patterns of past snow accumulation.

Some other pictures:

|

| Even the top of the mountains don't have any snow left in late summer |

|

| A beautiful example of wave ogives: Bulges that form each year at the bottom of some ice falls. |

|

| An ice marginal lake drained here. The water was released in a flood under the glacier. The stranded ice bergs on the side indicate how big the lake was. |

|

| Some floating ice bergs in the proglacial lake. |

|

| Mt. Fairweather in the distance |

|

|

|

|

On the way back we passed by

Hubbard Glacier. It is an advancing tidewater glacier and it is threatening to separate the two branches of the fjord visible in the picture. This would turn Russell Fjord (on the left) into a lake.